Service Navigation

Search

Precipitation falling in the form of ice balls is called hail. Hailstones form inside powerful and usually towering thunderclouds. This happens when the atmosphere is very unstable, with high humidity and strong updraughts (as in thunderstorms). In tall clouds, supercooled water (liquid water with a temperature below 0°C) freezes on small particles (aerosols) and ice particles known as hail embryos are formed.

How hailstones grow

If the updraughts within the thundercloud are strong enough, the hail embryos are carried upwards to where additional supercooled water can stick to them. The embryos can also fall to lower levels within the cloud, where water vapour freezes onto them and they continue to grow. As long as the updraughts are strong enough, the hailstones can be carried into the upper levels of the cloud several times over, where supercooled water freezes onto them again. This process repeats itself until the hailstone is so heavy that the updraughts can no longer carry it. It then falls towards the Earth's surface at a speed of 30 to 200 km/h, depending on its size.

Hail distribution in Switzerland

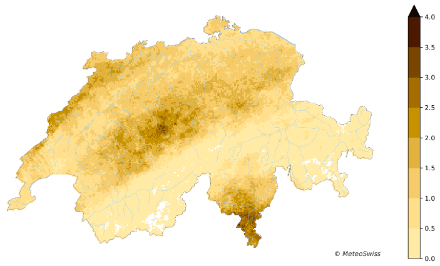

MeteoSwiss uses the Swiss weather radar network to monitor and analyse how frequently hail events occur in Switzerland and how large the hailstones are. Based on these measurements, MeteoSwiss provides maps and time series of the climatological distribution of hail, hail frequency and hail hazard. These are of great importance for risk assessment, prevention and planning in the insurance and construction industries, civil protection, agriculture and forestry.

Southern Ticino, the Napf region and the Jura are particularly affected by hail. In these areas, an average of two to four days of hail occur per square kilometre every year in the summer months. In the Alps, hail is rare. These findings are based on data from 2002 onwards. This period is too short to reliably ascertain whether hail frequency or hailstone size will change as a result of climate change.

The Swiss hail monitoring network

Since hailstorms are usually very localised and only occur for a short length of time, establishing an informative hail monitoring network is a major challenge. Radar measurements help to identify "hail hotspots" in Switzerland. In cooperation with Mobiliar Insurance, MeteoSwiss operates a unique monitoring network at ground-level weather stations in the "Swiss Hail Monitoring Network" project, in the areas with the highest likelihood of hail, which enables direct observation of the hailstones and their properties when they hit the sensors.

Since May 2015, it has also been possible to report hail events via the MeteoSwiss app. In the app, the user can enter whether hail was observed and how large the hailstones were. The combination of data from weather radar, the hail reporting function in the MeteoSwiss app and the hail monitoring network makes the MeteoSwiss approach unique worldwide and should help to improve the accuracy of hail information throughout Switzerland.