Service Navigation

Search

The first meteorological monitoring network

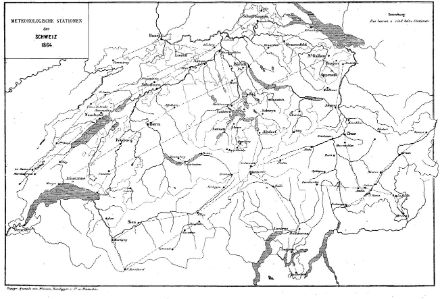

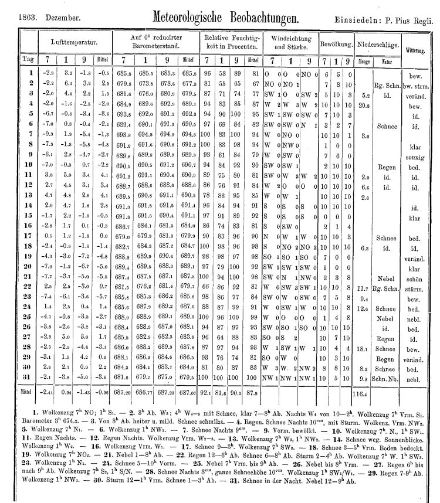

In Switzerland, instrumental meteorological monitoring dates back to the early 18th century, when the first measurements were conducted by Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672–1733), a physicist and mathematics professor in Zurich. However, it was not until December 1863 that systematic measurements began across Switzerland using standardised procedures and the same instruments at all stations.

The concept for the first meteorological observation network was developed under the guidance of the Swiss Society of Natural Sciences. Based on this concept and with the support of the United Federal Assembly, 88 stations across Switzerland were established and equipped. The network covered the main climate regions of the country, stretching from Geneva to St. Gallen, and from Basel to Brusio. It even included high-altitude areas, thanks to the hospices on the Alpine passes (e.g. Great St. Bernard, St. Gotthard, Grimsel).

Although the observation network was coordinated by and received financial support from the federal government, it initially remained a system of volunteers, who systematically observed the weather across Switzerland three times a day, every day of the year. The Swiss Society of Natural Sciences collated the data, which was used solely for climatological purposes. Only when the Central Swiss Meteorological Office (now the Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology) was established in 1881 did the professionalisation of staff and instruments begin in earnest. The station network was also expanded over the course of time. By the beginning of the 20th century, it already consisted of around 120 fully equipped climate stations and another 250 locations that monitored only the precipitation amount.

Automatic observations from 1981

The first automatic weather stations were introduced in Switzerland in 1981. From that point onwards, the stations sent the automatically recorded readings of various meteorological parameters every 10 minutes to a central computer at the Swiss Meteorological Institute, where the data was checked for plausibility and stored in digital archives. By the early 1990s, around 70 of these stations were in operation across Switzerland. Since the mid-2010s, all of the fully equipped climate stations operated by MeteoSwiss have been automated. Therefore, historically speaking, all of the weather information held in our archives from approximately the first 120 years is based on manually conducted observations and readings. This invaluable work was carried out by people like monks, teachers, farmers, weather enthusiasts, fortress and border guards, police officers, and many others who observed the weather day and night.

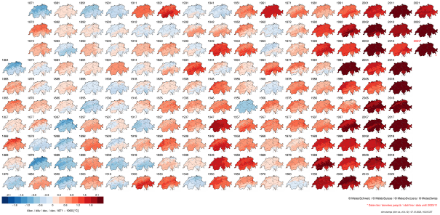

The importance of long measurement series

Many of the original 88 measurement stations are still in operation. Without these long measurement series, which now extend back more than 150 years, it would be impossible to track the climatic changes that have taken place in Switzerland since the Industrial Revolution to the present day. However, over time, stations have had to be relocated, sometimes more than once, such as when an observer changed or because it was not usually possible to install an automatic station at the site of the old weather instrument shelter. Before long-term trends can be analysed, the measurement series must be adjusted to remove the influence of such changes, a process achieved via the methodology of measurement series homogenisation.

From manual data gathering to automatic monitoring stations

Prior to 1981, all weather information in our country was collected manually. Both day and night, and in all weather conditions, important data was meticulously recorded by people such as monks, teachers, farmers, weather enthusiasts, fortress and border guards, police officers, and many others.

In the second half of the 19th century, there was a growing interest within meteorology to expand data collection to the vertical plane. Theoretically oriented meteorologists were pushing for the collection of observations from the higher layers of the atmosphere, hoping to gain new insights to better explain weather phenomena. However, 19th-century meteorological data collection relied on observers being on-site all year round and taking regular measurements. In the higher regions of Switzerland, such stations operated on permanently inhabited passes like the Great St. Bernard or the Gotthard. However, these measurements were not unaffected by local influences.

At the second International Meteorological Congress in Rome in 1879, a resolution was passed requesting Switzerland to establish an observatory on one of its high mountain peaks. At the suggestion of Robert Billwiler, the first head of the Central Swiss Meteorological Office, founded in 1881, the 2,500-meter-high Säntis was selected as the location. The summit of Säntis was relatively free-standing and accessible. In addition to receiving federal financial support, the establishment of a well-equipped station at the Säntis guesthouse was also supported by the Swiss Alpine Club, various natural science societies, and several cantonal governments. The station, which operated year-round, opened in September 1882.

Readings were taken from the instruments five times a day, and the observer was in daily contact with the Central Swiss Meteorological Office in Zurich via telegraph line. It soon became apparent, however, that the instruments housed on the upper floor of the guest house were impacted by vibrations, especially during busy summer weekends. So that the full scope of the scientific work on Säntis could be maximised, construction of an observatory began in 1886 and it became operational a year later.

When it opened in 1882, the Säntis station was the highest permanent meteorological monitoring station in Europe. During the 1880s, additional observatories were established, such as on the Pic du Midi in the Pyrenees and on the Sonnblick in the Eastern Alps. Along with data from the newly added balloon flights, these developments advanced the meteorological exploration of the upper air layers.

Source: Hupfer Franziska (2019): Das Wetter der Nation. Chronos Verlag, Zurich. ISBN 978-3-0340-1502-8