Service Navigation

Search

The development of meteorology in Switzerland is a fascinating journey through centuries of scientific progress and technological innovation. Switzerland has played a significant role in this field, from its earliest weather observations to modern forecasting methods.

- 1545–1576: First regular meteorological records in Zurich

- 1798: First Swiss weather station conducting regular observations in Geneva

- 1863: Establishment of 88 weather observation stations by the Swiss Society of Natural Sciences

- 1878: Start of publication of daily weather forecasts in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ)

- 1880: Founding of the Meteorologische Zentralanstalt (Swiss Meteorological Institute) (MZA)

- 1887: Establishment of the weather station on Säntis

- 1909: First comprehensive climatology of Switzerland

Timeline of key events

4th century BC

Aristotle attempted to explain the atmospheric processes. In the absence of meteorological measuring instruments, he confined his descriptions to the phenomena.

15th century

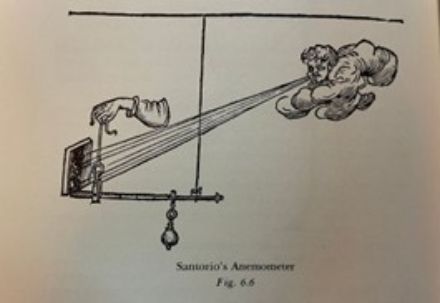

Around 1450, Leon Battista Alberti built the first anemometers, in which the movement of a wind vane provided an estimation of wind speed.

16th century

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) is thought to be the inventor of the hygrometer, a device for measuring humidity. Galileo Galilei (1564–1641) discovered the principles of temperature measurement, noting that the density of liquids changed with temperature.

Early weather observations

Meteorology in Switzerland began in the 16th century, when scholars started to observe and study natural phenomena more closely.

The oldest systematically recorded meteorological data in Switzerland was gathered by Wolfgang Haller, the custodian of the Grossmünster Church in Zurich. Spanning the years 1545 to 1576, these records provide a unique insight into Switzerland’s weather history during the third quarter of the 16th century.

In 1697, Zurich naturalist Johann Jakob Scheuchzer called for meteorological measurements to be conducted according to standardised rules in as many locations as possible. Although his appeal initially received little attention, in the 18th century, systematic observations began in several cities, such as Basel, and continued almost uninterrupted to the present day.

17th century

Evangelista Torricelli (1608–1647) invented the barometer (a device that measures air pressure). In 1647, Blaise Pascal discovered that air pressure decreased with altitude. The standard unit of pressure is named after him.

In the 17th century, Florentine scientists invented the thermometer (Galileo/Santorio) and the barometer (Torricelli), both of which are still in use today.

18th century

Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit invented the mercury thermometer and in 1714 defined the Fahrenheit temperature scale. Anders Celsius based his scale on the melting and boiling points of water, giving rise to the Celsius scale in 1742.

Around 1780, Geneva scientist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure invented the hair hygrometer, a device for measuring humidity, giving fresh impetus to meteorological research in Switzerland.

Swiss researchers began systematically measuring air pressure, temperature and humidity. However, up until the 19th century, the number of observation sites remained very limited, and the measurements were often sporadic, inaccurate and thus difficult to compare.

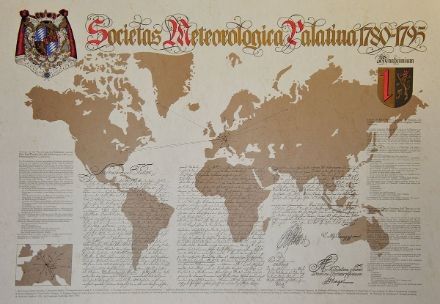

Societas Meteorologica Palatina

In 1780, Elector Karl Theodor founded the Societas Meteorologica Palatina in Mannheim, organising weather observations on a global scale for the first time, at 39 stations in different countries. Data were transmitted as per the technological standards of the time: the measurements were sent to Mannheim by horse and ship and then published in yearbooks. Due to political turmoil and the death of the Elector, the Societas Meteorologica Palatina ceased operations at the end of the 18th century.

19th century

The Geneva physicist Marc Auguste Pictet established Switzerland’s first two stations with regular weather observations – one in Geneva in 1798 and one on the Great St. Bernard in 1817.

In 1823, he proposed the establishment of the first observation network, consisting of 12 stations equipped with barometers and thermometers, to the Swiss Society of Natural Sciences. These stations were in operation from 1823 to 1837.

The collected data was not only of interest to scientists but also to the general public. As a result, several cantons decided to set up their own observation networks (Bern in 1830, Ticino in 1843 and Thurgau in 1855).

The growth in maritime trade increased the need for a standardised classification of wind strength. In 1806, Francis Beaufort distilled various approaches into the Beaufort scale, which describes the effects of different wind forces on land and at sea.

In the conflict-ridden 19th century, meteorological progress initially stagnated. Meanwhile, communication – a field becoming increasingly important for meteorology – was seeing a revolution in data transmission: In 1837, Samuel Morse invented his eponymous alphabet.

First systematic observations and forecasts in Switzerland

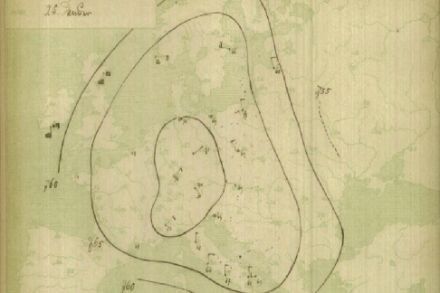

On 1 December 1863, the Swiss Society of Natural Sciences (Schweizerische Naturforschende Gesellschaft) established 88 observation stations with standardised rules and instruments. The results of these observations were published in annual reports.

On 1 June 1878, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) published the first daily weather forecasts, and soon after, other newspapers followed suit. The forecasts were based on Swiss observations and reports from the Paris Observatory.

First meteorological congress

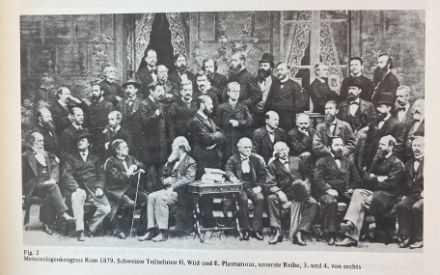

In 1873, the First Meteorological Congress established meteorological connections between nations.

In 1878, a meeting in Utrecht voted to institutionalise international collaboration. This resulted in the establishment of the International Meteorological Organization at a meteorologists’ conference in Rome in 1879. One of the founders of the organisation, and among its first chairmen, was Swiss scientist H. Wild, the then director of the Russian meteorological service.

Establishment of the Swiss Meteorological Institute (Meteorologische Zentralanstalt – MZA)

In 1880, the Swiss Federal Council passed a resolution to establish the Swiss Meteorological Institute (MZA). Operations officially began on 1 May 1881. Under the direction of R. Billwiller Sr., the new institute published

- daily weather reports with European weather maps

- an observation table

- an overview of the general weather situation

- and forecasts for the following day

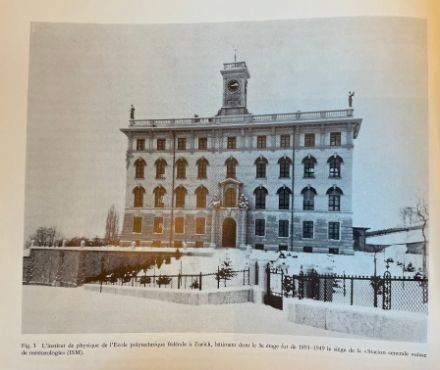

From the outset, the headquarters was located in Zurich, initially near the observatory. In 1891, the MZA relocated to the Institute of Physics at the Technical University. The offices consisted of about ten rooms, including accommodation for the observer. The premises also included a tower for wind measurements, a terrace for cloud and solar observations, and an instrument garden for measuring temperature, pressure, precipitation and snowfall. The number of staff initially increased from four to six in 1879. By 1900, there were eight employees, and by the start of the First World War, there were 14.

The observation network was soon expanded to include precipitation stations, forming a much denser network than the original one. The reason for this was that precipitation is much more irregularly distributed than temperature variations.

A significant advancement occurred around 1915 with the introduction of totalisers, i.e. automated measuring devices that allow for continuous data collection. Annual precipitation totals were read once a year in the autumn. Some of these instruments were also placed in higher-altitude areas, including glacier regions.

In addition to weather monitoring, the MZA conducted climatological observations and scientific research, publishing annual reports on topics such as the formation of foehn wind, or the causes of flooding. The reports attracted great interest from climate researchers, agriculture, water management and the emerging electrical industry.

In response to pressure from the International Meteorological Organisation, a weather station was set up on the peak of Säntis, at 2,500 m, and has been operating continuously since October 1887. A legacy of 125,000 Swiss francs from a childless business man from Schaffhausen enabled the construction of an observatory, where 12 observers, some accompanied by their wives, were employed until 1969.

Life Säntis was not without its dangers, and observers on the exposed peak sometimes faced winds of over 200 km/h.

More information about the interesting history of weather observation on Säntis can be found here:

Early climatological studies

It was not long before the earliest measurements were being analysed from a climatological perspective. An initial study was published in 1873, just ten years after the observation network was established. The first comprehensive climatology of Switzerland was published in 1909 and was based on a 37-year observation period (1864–1900).

Aerology and Alfred de Quervain

Alfred de Quervain, a very versatile scientist, made significant contributions to the advancement of aerological activities at the MZA. Among other things, he developed a special theodolite for tracking balloon probes and organised two Greenland expeditions. He also founded the Swiss Seismological Service.

Polar front theory

In the 1920s, the science behind weather forecasting was revolutionised by Norwegian electrodynamicist Vilhelm Bjerknes’ polar front theory. The Swiss Meteorological Institute was one of the first institutions outside Scandinavia to adopt this theory.