Service Navigation

Search

Frosty temperatures in spring, particularly at ground level, are especially hazardous for agriculture. Damage to young shoots and plants can mean serious loss of income for farmers, which is why frost warnings for agriculture are part of the standard remit of weather services in countries that are affected by spring frosts.

Blasts of cold air and the tradition of the Ice Saints

Spring frosts have been a regular occurrence for centuries in Central Europe, giving rise to the traditional belief that a blast of cold air often arrives in the region in the middle of May. Over time, this piece of weather lore became known as the Ice Saints. A regularly occurring weather pattern or singularity is defined as a deviation from the average annual course of meteorological elements that occurs on certain days in the annual calendar with reasonable regularity.

The dates of the Ice Saints

It is thought that the dates associated with this tradition originated during the Middle Ages. Descriptions in the literature refer to the Ice Saints falling on 11th to 14th May. These are the name days of St Mamertus, St Pancras, St Servatius and St Boniface. To conclude the cold snap, Cold Sophie arrives on 15th May. According to weather lore, once the Ice Saints have passed, frost will no longer pose a threat to agriculture. With the Gregorian calendar shift of 1582, the Ice Saints dates also moved forward, although this is often not accounted for in the literature. Taking this calendar reform into consideration, the Ice Saints days start on 19th May, with Cold Sophie falling on 23rd May.

Frost no more frequent than at other times in May

The Ice Saints singularity can be checked against the frequency of frost occurring in spring. In order to do this, it is necessary to have access to long-series temperature measurements taken just above ground level. The longest data series for temperatures 5 cm above the ground date back to 1965, and originate from the Geneva-Cointrin, Payerne and Zurich-Kloten weather stations. Analysis of these data series for the months of April and May clearly shows that, over the long-term average, frost directly above the soil (i.e. ground frost) is only a regular occurrence up until the middle of April. After that, the frequency with which ground frost occurs progressively declines to almost zero by the end of May.

There is no evidence of ground frost being more common during the Ice Saints period of 19th–23rd May. At weather stations with shorter data series, too, observations do not indicate that ground frost occurs more regularly over the Ice Saints period. We can conclude, therefore, that there is no evidence in Switzerland to confirm the Ice Saints as a period in May when ground frost is more common.

Ice Saints long since absent

The fact that ground frost occurs with fairly equal regularity throughout the month of May has been known for over 100 years. In his very comprehensive textbook on meteorology published in 1906, Julius Hann cites a number of studies indicating that the Ice Saints days do not pose any greater risk of frost than the rest of May. Many of these studies were conducted in the second half of the 19th century, while in the first half of the 20th century, long-term records of frost damage from eastern Switzerland show that no concentration of ground frost around the Ice Saints period can be identified.

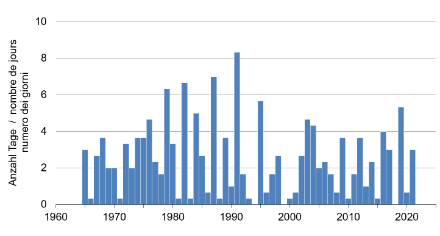

Ground frost occurs at least once in May every year

Even if the Ice Saints lore in its strictest sense of ground frost occurring around a certain date in May cannot be confirmed as a clear climatic phenomenon on the Swiss plateau, ground frost is nevertheless a regular occurrence throughout May as a whole. In the observation period from 1965 for the Swiss plateau, ground frost occurred at least once or twice in May every year, and in around 40% of the years there were more than two days in May with ground frost.

References

- Blüthgen, J., Weischet, W., 1980: Allgemeine Klimageographie. (General Climate Geography.) 3rd edition. From the series Textbook of General Geography. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York.

- Hann, J., 1906: Lehrbuch der Meteorologie. (Textbook of Meteorology.) Second edition, revised. Tauchnitz-Verlag, Leipzig.

- Primault, B., 1971: Du risque de gel et de sa prévision. (Ice hazard and prevention.) Publications of the Central Swiss Meteorological Office, No. 20, Zurich.

- Schirmer H., 1987: Meyers kleines Lexikon Meteorologie. (Meyer’s Little Meteorology Dictionary.) Meyers Lexikonverlag. Mannheim, Wien, Zurich.

- Schüepp, Max, 1950: Wolken, Wind und Wetter. (Clouds, Wind and Weather.) Büchergilde Gutenberg, Zurich.